And just like that, T-Mobile is already celebrating the eighth year of its T-Mobile Tuesdays program. With such a big celebration in place, the Un-carrier unveiled its big rewards for customers. After eight years and 400 Tuesdays since its inception, T-Mobile Tuesdays has a weeklong “Thankiversary.” Starting on Tuesday, June 4th, T-Mobile Tuesdays has these deals in store: Celebr8tion-worthy prizes: T-Mobile is serving up eight massive prizes for eight lucky customers — including $80,000 cash, $8,000 in ... [read full article]

The post T-Mobile Tuesdays Celebrates 8th Anniversary With Awesome Offers appeared first on TmoNews.

In April 2020, we blogged about how to get COBOL running on Cloudflare Workers by compiling to WebAssembly. The ecosystem around WebAssembly has grown significantly since then, and it has become a solid foundation for all types of projects, be they client-side or server-side.

As WebAssembly support has grown, more and more languages are able to compile to WebAssembly for execution on servers and in browsers. As Cloudflare Workers uses the V8 engine and supports WebAssembly natively, we’re able to support languages that compile to WebAssembly on the platform.

Recently, work on LLVM has enabled Fortran to compile to WebAssembly. So, today, we’re writing about running Fortran code on Cloudflare Workers.

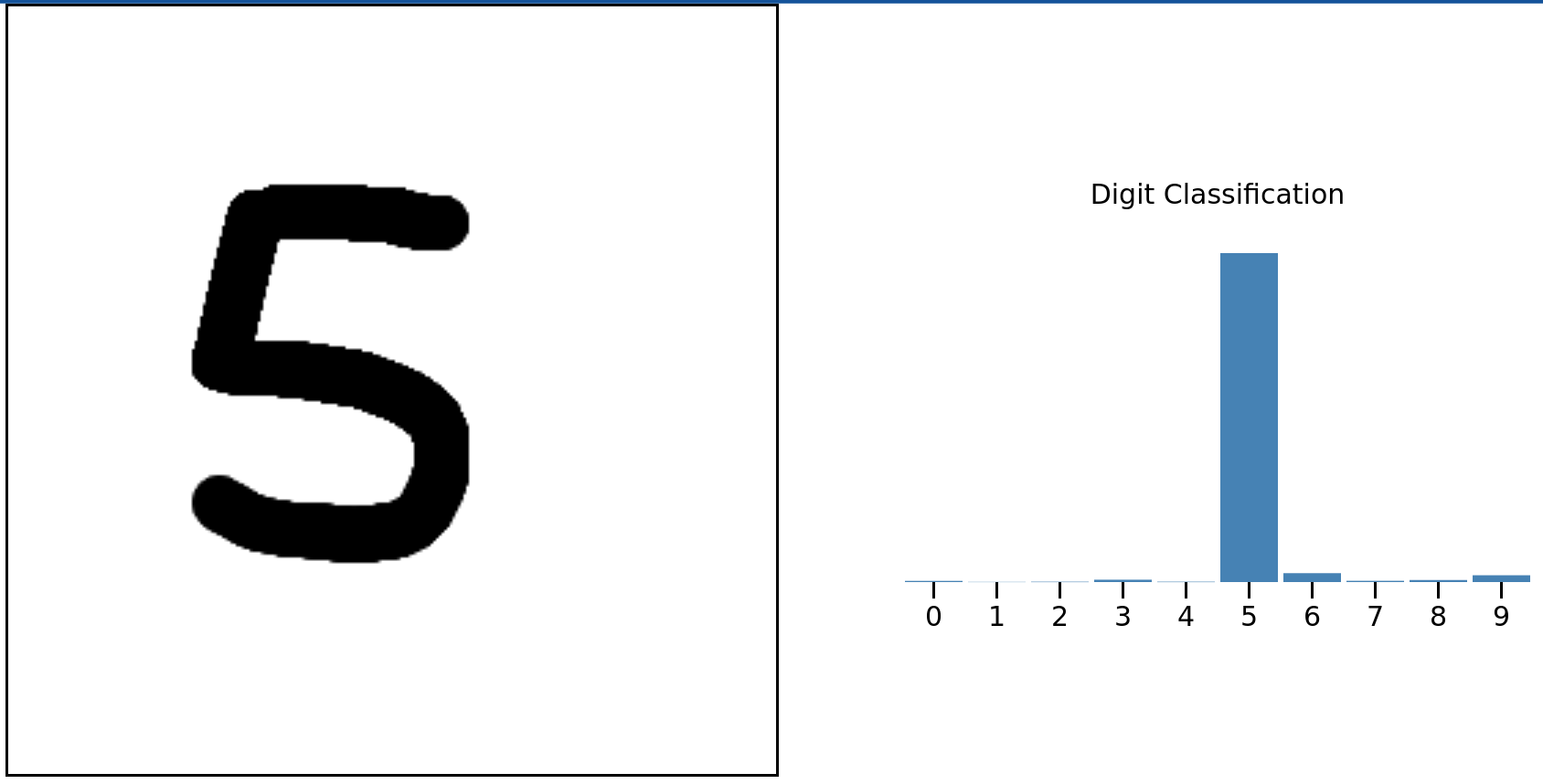

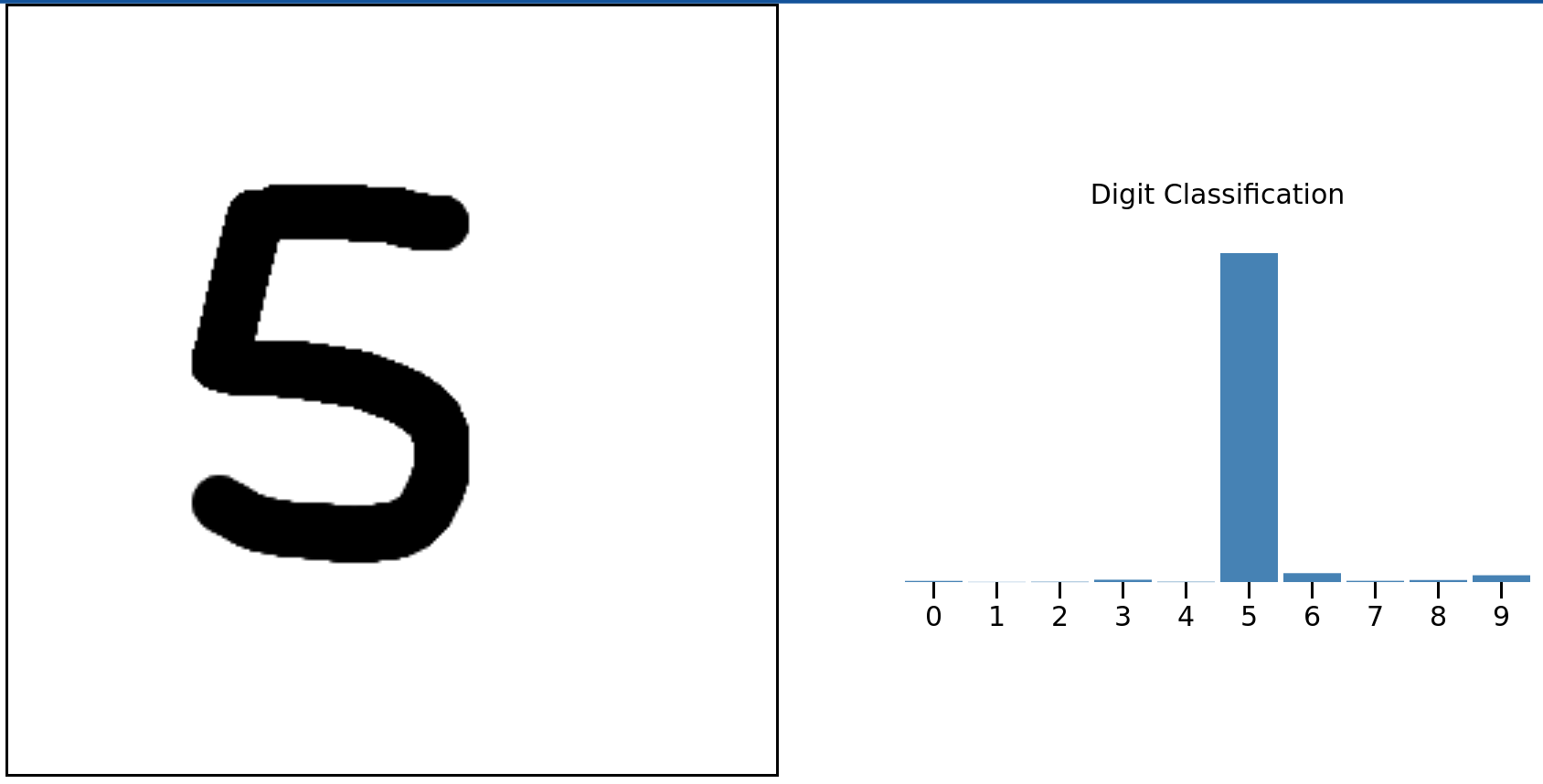

Before we dive into how to do this, here’s a little demonstration of number recognition in Fortran. Draw a number from 0 to 9 and Fortran code running somewhere on Cloudflare’s network will predict the number you drew.

Try yourself on handwritten-digit-classifier.fortran.demos.cloudflare.com.

This is taken from the wonderful Fortran on WebAssembly post but instead of running client-side, the Fortran code is running on Cloudflare Workers. Read on to find out how you can use Fortran on Cloudflare Workers and how that demonstration works.

Wait, Fortran? No one uses that!

Not so fast! Or rather, actually pretty darn fast if you’re doing a lot of numerical programming or have scientific data to work with. Fortran (originally FORmula TRANslator) is very well suited for scientific workloads because of its native functionality for things like arithmetic and handling large arrays and matrices.

If you look at the ranking of the fastest supercomputers in the world you’ll discover that the measurement of “fast” is based on these supercomputers running a piece of software called LINPACK that was originally written in Fortran. LINPACK is designed to help with problems solvable using linear algebra.

The LINPACK benchmarks use LINPACK to solve an n x n system of linear equations using matrix operations and, in doing so, determine how fast supercomputers are. The code is available in Fortran, C and Java.

A related Fortran package, BLAS, also does linear algebra and forms the basis of the number identifying code above. But other Fortran packages are still relevant. Back in 2017, NASA ran a competition to make FUN3D (used to perform calculations of airflow over simulated aircraft). FUN3D is written in Fortran.

So, although Fortran (or at the time FORTRAN) first came to life in 1957, it’s alive and well and being used widely for scientific applications (there’s even Fortran for CUDA). One particular application left Earth 20 years after Fortran was born: Voyager. The Voyager probes use a combination of assembly language and Fortran to keep chugging along.

But back in our solar system, and back on Region: Earth, you can now use Fortran on Cloudflare Workers. Here’s how.

How to get your Fortran code running on Cloudflare Workers

To make it easy to run your Fortran code on Cloudflare Workers, we created a tool called Fortiche (translates to smart in French). It uses Flang and Emscripten under the hood.

Flang is a frontend in LLVM and, if you read the Fortran on WebAssembly blog post, we currently have to patch LLVM to work around a few issues.

Emscripten is used to compile LLVM output and produce code that is compatible with Cloudflare Workers.

This is all packaged in the Fortiche Docker image. Let’s see a simple example.

add.f90:

SUBROUTINE add(a, b, res)

INTEGER, INTENT(IN) :: a, b

INTEGER, INTENT(OUT) :: res

res = a + b

END

Here we defined a subroutine called add that takes a and b, sums them together and places the result in res.

Compile with Fortiche:

docker run -v $PWD:/input -v $PWD/output:/output xtuc/fortiche --export-func=add add.f90

Passing --export-func=add to Fortiche makes the Fortran add subroutine available to JavaScript.

The output folder contains the compiled WebAssembly module and JavaScript from Emscripten, and a JavaScript endpoint generated by Fortiche:

$ ls -lh ./output

total 84K

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 392 avril 22 12:00 index.mjs

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 27K avril 22 12:00 out.mjs

-rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 49K avril 22 12:00 out.wasmAnd finally the Cloudflare Worker:

// Import what Fortiche generated

import {load} from "../output/index.mjs"

export default {

async fetch(request: Request): Promise<Response> {

// Load the Fortran program

const program = await load();

// Allocate space in memory for the arguments and result

const aPtr = program.malloc(4);

const bPtr = program.malloc(4);

const outPtr = program.malloc(4);

// Set argument values

program.HEAP32[aPtr / 4] = 123;

program.HEAP32[bPtr / 4] = 321;

// Run the Fortran add subroutine

program.add(aPtr, bPtr, outPtr);

// Read the result

const res = program.HEAP32[outPtr / 4];

// Free everything

program.free(aPtr);

program.free(bPtr);

program.free(outPtr);

return Response.json({ res });

},

};

Interestingly, the values we pass to Fortran are all pointers, therefore we have to allocate space for each argument and result (the Fortran integer type is four bytes wide), and pass the pointers to the `add` subroutine.

Running the Worker gives us the right answer:

$ curl https://fortran-add.cfdemos.workers.dev

{"res":444}

You can find the full example here.

Handwritten digit classifier

This example is taken from https://gws.phd/posts/fortran_wasm/#mnist. It relies on the BLAS library, which is available in Fortiche with the flag: --with-BLAS-3-12-0.

Note that the LAPACK library is also available in Fortiche with the flag: --with-LAPACK-3-12-0.

You can try on https://handwritten-digit-classifier.fortran.demos.cloudflare.com and find the source code here.

Let us know what you write using Fortran and Cloudflare Workers!

Google Security Blog:

In 2023, we prevented 2.28 million policy-violating apps from being published on Google Play in part thanks to our investment in new and improved security features, policy updates, and advanced machine learning and app review processes. We have also strengthened our developer onboarding and review processes, requiring more identity information when developers first establish their Play accounts. Together with investments in our review tooling and processes, we identified bad actors and fraud rings more effectively and banned 333K bad accounts from Play for violations like confirmed malware and repeated severe policy violations.

Additionally, almost 200K app submissions were rejected or remediated to ensure proper use of sensitive permissions such as background location or SMS access.

App stores are just greedy monopolies, am I right?

When Marianne Smith was teaching computer science in 2016 at Flathead Valley Community College, in Kalispell, Mont., the adjunct professor noticed the female students in her class were severely outnumbered, she says.

Smith says she believed the disparity was because girls were not being introduced to science, technology, engineering, and mathematics in elementary and middle school.

Code Girls United

Founded

2018

Headquarters

Kalispell, Mont.

Employees

10

In 2017 she decided to do something to close the gap. The IEEE member started an after-school program to teach coding and computer science.

What began as a class of 28 students held in a local restaurant is now a statewide program run by Code Girls United, a nonprofit Smith founded in 2018. The organization has taught more than 1,000 elementary, middle, and high school students across 38 cities in Montana and three of the state’s Native American reservations. Smith has plans to expand the nonprofit to South Dakota, Wisconsin, and other states, as well as other reservations.

“Computer science is not a K–12 requirement in Montana,” Smith says. “Our program creates this rare hands-on experience that provides students with an experience that’s very empowering for girls in our community.”

The nonprofit was one of seven winners last year of MIT Solve’s Gender Equity in STEM Challenge. The initiative supports organizations that work to address gender barriers. Code Girls United received US $100,000 to use toward its program.

“The MIT Solve Gender Equity in STEM Challenge thoroughly vets all applicants—their theories, practices, organizational health, and impact,” Smith says. “For Code Girls United to be chosen as a winner of the contest is a validating honor.”

From a restaurant basement to statewide programs

When Smith had taught her sons how to program robots, she found that programming introduced a set of logic and communication skills similar to learning a new language, she says.

Those skills were what many girls were missing, she reasoned.

“It’s critical that girls be given the opportunity to speak and write in this coding language,” she says, “so they could also have the chance to communicate their ideas.”

An app to track police vehicles

Last year Code Girls United’s advanced class held in Kalispell received a special request from Jordan Venezio, the city’s police chief. He asked the class to create an app to help the Police Department manage its vehicle fleet.

The department was tracking the location of its police cars on paper, a process that made it challenging to get up-to-date information about which cars were on patrol, available for use, or being repaired, Venezio told the Flathead Beacon.

The objective was to streamline day-to-day vehicle operations. To learn how the department operates and see firsthand the difficulties administrators faced when managing the vehicles, two students shadowed officers for 10 weeks.

The students programmed the app using Visual Studio Code, React Native, Expo Go, and GitHub.

The department’s administrators now more easily can see each vehicle’s availability, whether it’s at the repair shop, or if it has been retired from duty.

“It’s a great privilege for the girls to be able to apply the skills they’ve learned in the Code Girls United program to do something like this for the community,” Smith says. “It really brings our vision full circle.”

At first she wasn’t sure what subjects to teach, she says, reasoning that Java and other programming languages were too advanced for elementary school students.

She came across MIT App Inventor, a block-based visual programming language for creating mobile apps for Android and iOS devices. Instead of learning a coding language by typing it, students drag and drop jigsaw puzzle–like pieces that contain code to issue instructions. She incorporated building an app with general computer science concepts such as conditionals, logic flow, and variables. With each concept learned, the students built a more difficult app.

“It was perfect,” she says, “because the girls could make an app and test it the same day. It’s also very visual.”

Once she had a curriculum, she wanted to find willing students, so she placed an advertisement in the local newspaper. Twenty-eight girls signed up for the weekly classes, which were held in a diner. Assisting Smith were Beth Schecher, a retired technical professional; and Liz Bernau, a newly graduated elementary school teacher who taught technology classes. Students had to supply their own laptop.

At the end of the first 18 weeks, the class was tasked with creating apps to enter in the annual Technovation Girls competition. The contest seeks out apps that address issues including animal abandonment, safely reporting domestic violence, and access to mental health services.

The first group of students created several apps to enter in the competition, including ones that connected users to water-filling stations, provided people with information about food banks, and allowed users to report potholes. The group made it to the competition’s semifinals.

The coding program soon outgrew the diner and moved to a computer lab in a nearby elementary school. From there classes were held at Flathead Valley Community College. The program continued to grow and soon expanded to schools in other Montana towns including Belgrade, Havre, Joliet, and Polson.

The COVID-19 pandemic prompted the program to become virtual—which was “oddly fortuitous,” Smith says. After she made the curriculum available for anyone to use via Google Classroom, it increased in popularity.

That’s when she decided to launch her nonprofit. With that came a new curriculum.

What began as a class of 28 students held in a restaurant in Kalispell, Mont., has grown into a statewide program run by Code Girls United. The nonprofit has taught coding and computer science to more than 1,000 elementary, middle, and high school students. Code Girls United

What began as a class of 28 students held in a restaurant in Kalispell, Mont., has grown into a statewide program run by Code Girls United. The nonprofit has taught coding and computer science to more than 1,000 elementary, middle, and high school students. Code Girls United

Program expands across the state

Beginner, intermediate, and advanced classes were introduced. Instructors of the weekly after-school program are volunteers and teachers trained by Smith or one of the organization’s 10 employees. The teachers are paid a stipend.

For the first half of the school year, students in the beginner class learn computer science while creating apps.

“By having them design and build a mobile app,” Smith says, “I and the other teachers teach them computer science concepts in a fun and interactive way.”

Once students master the course, they move on to the intermediate and advanced levels, where they are taught lessons in computer science and learn more complicated programming concepts such as Java and Python.

“It’s important to give girls who live on the reservations educational opportunities to close the gap. It’s the right thing to do for the next generation.”

During the second half of the year, the intermediate and advanced classes participate in Code Girls United’s App Challenge. The girls form teams and choose a problem in their community to tackle. Next they write a business plan that includes devising a marketing strategy, designing a logo, and preparing a presentation. A panel of volunteer judges evaluates their work, and the top six teams receive a scholarship of up to $5,000, which is split among the members.

The organization has given out more than 55 scholarships, Smith says.

“Some of the girls who participated in our first education program are now going to college,” she says. “Seventy-two percent of participants are pursuing a degree in a STEM field, and quite a few are pursuing computer science.”

Introducing coding to Native Americans

The program is taught to high school girls on Montana’s Native American reservations through workshops.

Many reservations lack access to technology resources, Smith says, so presenting the program there has been challenging. But the organization has had some success and is working with the Blackfeet reservation, the Salish and Kootenai tribes on the Flathead reservation, and the Nakota and Gros Ventre tribes at Fort Belknap.

The workshops tailor technology for Native American culture. In the newest course, students program a string of LEDs to respond to the drumbeat of tribal songs using the BBC’s Micro:bit programmable controller. The lights are attached to the bottom of a ribbon skirt, a traditional garment worn by young women. Colorful ribbons are sewn horizontally across the bottom, with each hue having a meaning.

The new course was introduced to students on the Flathead reservation this month.

“Montana’s reservations are some of the most remote and resource-limited communities,” Smith says, “especially in regards to technology and educational opportunities.

“It’s important to give girls who live on the reservations educational opportunities to close the gap. It’s the right thing to do for the next generation.”